The Maeght Foundation was born from the desire of the couple formed by Aimé and Marguerite Maeght to have a place to present modern and contemporary art in all its visual aspects. It was conceived as a meeting place where artists friends of the family could work and exhibit their pieces. The architectural ensemble is inspired by Antoni Miró’s studio, a work that aroused great interest in the couple and that was built in 1950 by the architect to whom they would later entrust their project: the first private European art foundation. However, although the contacts between Josep LLuís Sert and Aimé Maeght did not begin until 1964, their constant and close dialogue was decisive in conceiving a Mediterranean architecture dedicated to both artists and art lovers.

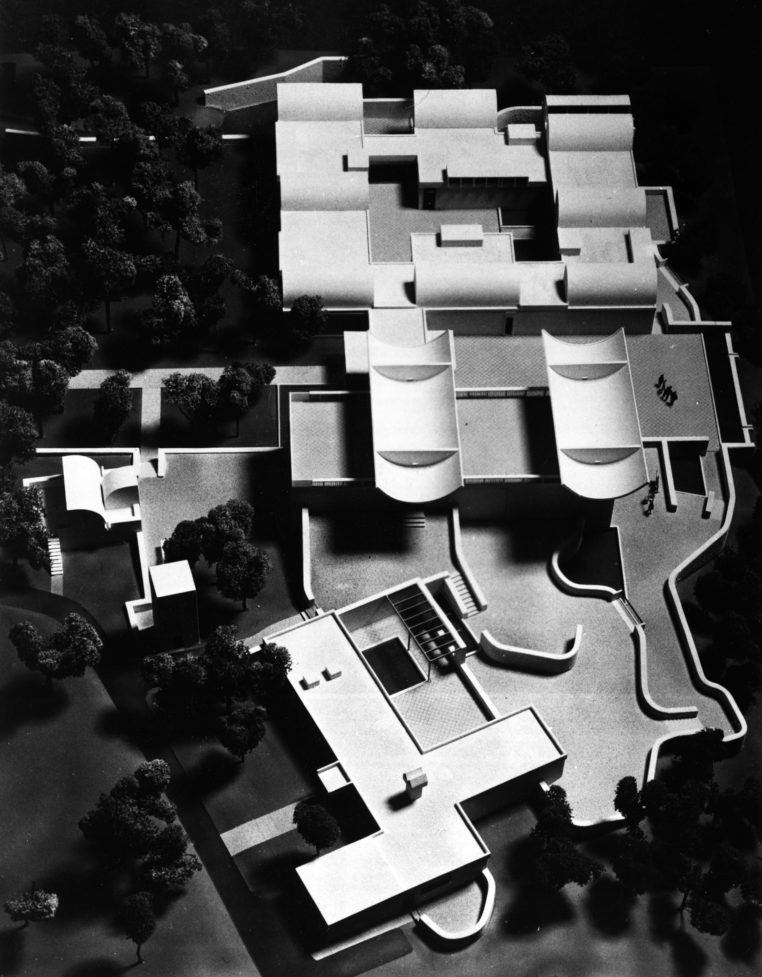

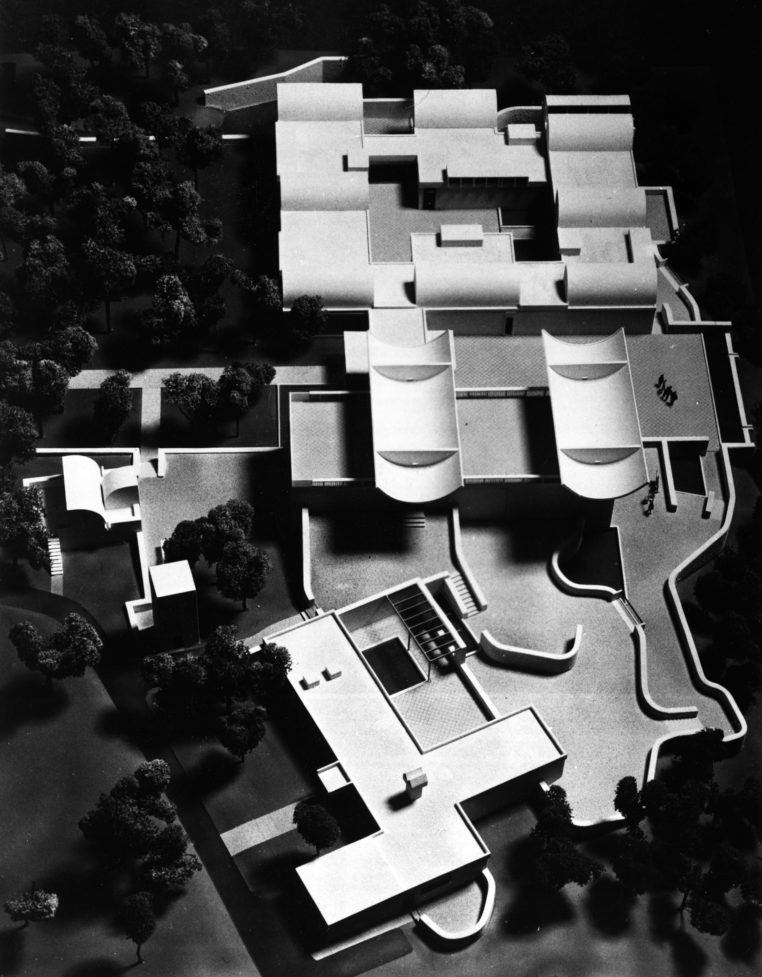

The site, on a hill full of pines near Saint-Paul de Vence, with privileged views of the Alps, the Mediterranean Sea and Cape Antibes, proposed an important use of outdoor spaces. That is why the project decidedly bets on working on a scale intimately related to the environment, articulating spaces and volumes in a way similar to a village. The complex consists of three main buildings connected and organised by means of courtyards and gardens, which are also projected as places designed for the exhibition. In this way, the artists contributed works conceived expressly for these spaces, achieving, moreover, a close collaboration between them from their first sketches.

Town Hall and Cloister

Located in the eastern part of the parcel, the two exhibition pavilions known as the Town Hall or “la Mairie” and the Cloister are the first pieces to be shown to the visitor when the tour begins. Also, they are the volumes that instantly capture attention both for their size and for their architectural qualities.

The single-height body or Cloister contains the permanent exhibition halls dedicated to artists friends of the family, such as Braque, Miró, Chagall and Kandinsky. Each room is specially designed to exhibit the works of these authors, including the treatment of indirect light, which penetrates through large skylights and brings rhythm and scale to the architecture.

In contrast, the City Hall, which has two large inverted vaults as a roof, constitutes the highest body and is located to the west of the entrance hall. Thus, a visual separation between the museum itself and the Miró Labyrinth is created, which can be entered from the first floor. Due to its size, this building houses a conference room and another for large exhibitions, as well as a library, among other rooms.

Director’s House

The Director’s House appears as the most important building built after the exhibition pavilions. Its situation helps to gain privacy through the connection with the Miró Labyrinth and the turn with respect to the Town Hall. Numerous parallels are established between the two constructions, as in a passage from the public scale to the domestic one. So, the architect’s mastery for the treatment of light, the expressiveness of the materials and the warmth of the spaces is shown.

The dwelling is arranged in two nuclei connected by a large interior space that, although displaced from the axis, constitutes the centre of the building. It connects the two façades and articulates all the spaces around it. Both nuclei are in turn divided into an interior space and an exterior one of equal proportions. Through the treatment of the wall, the vegetation and the pergolas, endow the complex with the Mediterranean character of Sert’s architecture.

Access to the complex is from the northwest, far from the museum. The overhang and the stairs at the entrance lead to the first nucleus where the rooms, office and bathrooms are located, linked to an external living space. From this first zone, one passes to the heart of the house, a diaphanous space where light and ceramic flooring take centre stage.

Chapel

The idea of building a chapel arose after the planimetric survey previous to the choice of sites for each building of the foundation. However, during this process the ruins of an old chapel dedicated to Saint Bernard were found. This was the main reason for Marguerite Maeght to decide to rebuild it, doing so in memory of her son Bernard Maeght, who died a few years earlier.

The space of this small architectural piece is illuminated by two of Sert’s characteristic skylights and contains a stained glass window created by Braque, as well as a medieval crucifix donated by the Spanish designer Balenciaga.

Cafe and ticket office

The novelty of having a cafeteria had clear and significant associations. For the architect himself, the café was a place of conviviality and creativity, and in his own words he expressed “the talks in the cafés of Paris had meant more to modern art in the last hundred years than all the schools put together”.

Similarly, the need for control and security in the face of the influx of visitors resulted in a small building next to the cafe. That generated a surveillance point previous to the entrance of the foundation.

The varied range of ceramic pieces that cover both the interior and exterior flooring could well summarise the uses of each room, as they allow the spaces to be differentiated, while at the same time unifying the floor plan through materiality. The tiles that make up the floor are handmade from terracotta from French Provence.

Marguerite et Aimé Maeght

Josep Lluís Sert

K. Bastlund

J. Zalewski

Site direction: Bellini, Lizero, Gozzi

Véra Cardot – Pierre Joly

© Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

Chemin des Gardettes, 623. Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 06570, France